How is comparative effectiveness research being used for decision-making in orthopaedics, and what does the future hold?

Comparative effectiveness research (CER) refers to assessing the body of evidence that compares the benefits and harms of different treatment methods. What differentiates CER from traditional medical research is that CER is demand driven. In other words, only when the demand for a procedure or technology grows to the point of significant budget impact will CER be performed. A confluence of factors at both the Federal and state level are raising the profile of CER and taking it from the academic to the health policy realm. These factors include:

- The growing role of government as the primary payer of medical services

- The pressure to reduce a ballooning Federal deficit

- State fiscal shortfalls/crises from recession-depleted coffers

- A sharp increase in Medicaid enrollees due to both the recession and healthcare legislation

- Comparative data starting to emerge from Federally funded CER projects

These price pressures, combined with emerging results that in many cases underscore a dearth of evidence supporting expensive technologies, are drawing increased attention to the power of CER to provide cover for difficult resource allocation decisions.

CER in Theory: The Push for CER in Orthopaedics

While comparative analyses between different pharmaceutical treatments have been common for some time, critical appraisals of surgical techniques and devices have rarely been performed. A major reason for the lack of rigorous comparisons in the surgical literature is, in large part, due to the difference in clearance pathways for devices. Over 90 percent of the devices on the market were clearance through the 510(k) process that requires limited evidence for clearance. This evidence is usually in the form of case series, most of which are retrospective and do not have the rigorous independent assessment of outcomes that would allow meaningful comparisons among products.

The U.S. market for spinal implants and devices used in spinal surgery grew about 11 percent between 2008 and 2009 to over $6.8 billion.1 The U.S. spine market for 2009 is about 30 times larger than the $225 million dollars reported for 1994.2 The U.S. hip and knee implant market grew 7.6 percent between 2007 and 2008 to about $6.1 billion.3 Given this continued expansion of orthopaedic volumes, calls for a more rigorous assessment of outcomes in orthopaedics are growing.

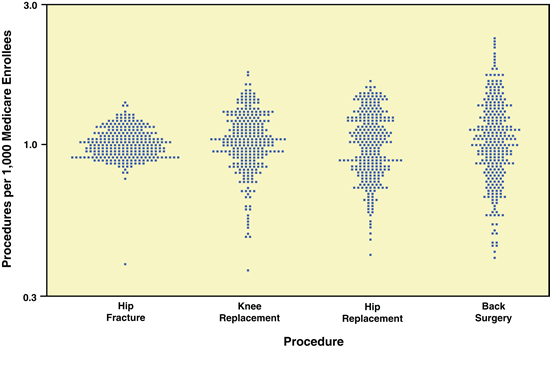

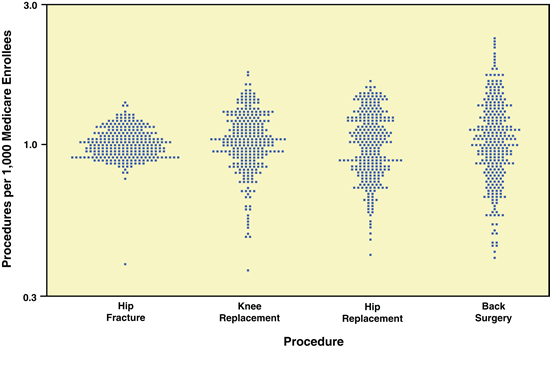

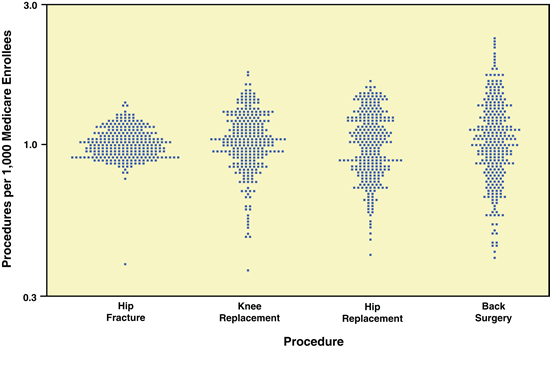

In 2007, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) published a report on opportunities to use CER for healthcare decision-making. The CBO report includes data from The Dartmouth Atlas group showing the degree of geographic variation in treatment patterns for four orthopaedic procedures: hip fracture, knee and hip replacement and back surgery. (See Exhibit 1.) There was little regional variation from the mean in hospitalization rates for patients with hip fractures, a diagnosis that would be made with little disagreement among providers. Variation was greater for rates of hip and knee replacements, in which the decision to have surgery can be based on numerous factors. The fourth procedure, back surgery, showed the largest regional variation by far. Data such as these raise questions about the role of physician judgment and whether better evidence on the appropriateness of procedures for different patients could reduce inappropriate care and costs.

Exhibit 1: Rates of Four Orthopaedic Procedures among Medicare Enrollees, 2002 and 2003(Standardized discharge ratio, log scale)

Source: Dartmouth Atlas Project, The Dartmouth Atlas of Health Care

Notes: In the figure, each point represents a hospital referral region; the country was divided into about 300 such regions on the basis of where Medicare enrollees typically receive hospital care. The points indicate how the rate at which the procedure is performed (per 1,000 Medicare enrollees) in each referral region compares with the national average rate (which has been normalized to 1.0). Differences in procedure rates were adjusted to account for differences among regions in the age, sex, and race of enrollees and for measures of illness rates.

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) has also joined the call for establishing greater evidence for orthopaedic procedures. Some of the funding for CER in the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act (ARRA) of 2009 went to the IOM to establish a list of 100 priority areas for research. Included in the IOM’s list were recommendations to:

- Establish a prospective registry to compare the effectiveness of treatment strategies for low back pain without neurological deficit or spinal deformity

- Compare the effectiveness of treatment strategies (e.g., artificial cervical discs, spinal fusion, pharmacologic treatment with physical therapy) for cervical disc and neck pain

There are signs that the above drivers of CER are already exerting influence in orthopaedics. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), the health research arm of the Department of Health and Human Services, awarded a grant to the Professional Society Coalition on Lumbar Fusion Outcomes to assemble a multi-stakeholder meeting to provide the foundation for a prospective registry of treatment modalities for spinal conditions. The Coalition includes representatives from all major spinal professional societies, including the American Association of Neurological Surgeons, the Congress of Neurological Surgeons, the Scoliosis Research Society and the North American Spine Society. The coalition is developing consensus on a framework for conducting CER in spinal conditions, including choice of outcome measures and overcoming the legal, financial and technical hurdles to such research.

Over the next few years, as Federally funded projects in orthopaedics are awarded and completed, this comparative data will enter the public realm.

Events at the Federal Level

These questions about the efficacy and appropriateness of orthopaedic procedures are being raised at a time of growing financial pressures on Federal healthcare spending. Total healthcare spending, which accounted for about eight percent of the U.S. economy in 1975, currently accounts for about 16 percent of gross domestic product. This share is projected to reach nearly 20 percent by 2016, absent any changes in payment or coverage.4

Over the long term, rising health care costs will be the single greatest contributor to government spending deficits. About half of all healthcare spending in the U.S. is publicly funded. In an attempt to gain control over these spiraling costs, Congress has looked to comparative outcomes assessment as a way to set spending priorities.

- ARRA funding allotted $1.1 billion for CER

- The health reform legislation established an ongoing national program in CER: the Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute, that will receive about $500 million per year starting in 2014

- Healthcare reforms have also funded pilot projects in Medicare to link payment to outcomes

National policy experts have proposed incorporating CER into Medicare payment by encouraging Medicare to pay equally for treatments that offer comparable outcomes. Thus, new technologies would not be able to command premium reimbursement unless the treatment could be proven to provide superior outcomes.5

A View from the States

Under the new healthcare law, an additional 40 million Americans will now be covered, mostly through the expansion of Medicaid programs. This increase in Medicaid enrollment is coming at a time when states are facing a $137 billion shortfall over the next two years. As pointed out by the National Governor’s Association (NGA), the countercyclical nature of Medicare expansion stresses state budgets as each one percent increase in the national unemployment rate is associated with an additional one million Medicaid recipients.6

Spending on Medicaid grew by 7.9 percent in 2009 and now accounts for 22 percent of state budgets. The NGA predicts a 21 percent increase in the number of Medicaid enrollees from 2008 to 2011. Covering these additional Medicaid enrollees will require $20 billion more over the next decade, according to the Congressional Budget Office.7 The CBO states that Medicare spending per enrollee continues to rise sharply, as well, primarily driven by the spreading use of new medical technology.

With millions of new recipients and with the costs per enrollee spiraling upwards, states will inevitably try to restrict coverage where possible. One model that other states may emulate is the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) committee established in the state of Washington. This group, comprising physicians and healthcare experts, reviews the available evidence on new technologies to determine not only the safety and efficacy, but the cost effectiveness of devices and procedures, as well. The committee then recommends whether the state should cover the technology fully, cover it under certain conditions or deny coverage entirely. Public payers in Washington must follow any recommendation made the HTA committee.

For the eight procedures evaluated in orthopaedic and related areas, three were denied coverage (discography, arthroscopic knee surgery for osteoarthritis and spinal cord stimulation for chronic neuropathic pain). The others (lumbar fusion, artificial discs, bone growth stimulators, hip resurfacing, and viscosupplementation) were covered under certain conditions. Decisions on three other procedures (total knee arthroplasty, vertebroplasty/kyphoplasty/sacroplasty and spinal injections) are pending.8

The financial impact of the Washington HTA committee is difficult to quantify. One estimate suggests a conservative savings of $21 million at a cost of $1 million.9 However, it is hard to estimate downstream costs and cost savings without a longer-term formal evaluation.

CER in Practice: In the Private Sector

There are several private sector organizations that review technologies. The most prominent is the Technology Evaluation Center that is part of the Blue Cross/Blue Shield Association. Its reviews are based on the available literature, with more weight given to studies that are judged to be of higher methodological quality. The center produces about 20 to 25 new assessments of drugs, devices, and other technologies each year; the analyses consider clinical effectiveness but generally do not assess cost effectiveness.

Some for-profit private-sector firms also specialize in technology assessments. Hayes, Inc., is one example. Organizations that are similar, but operate as nonprofits, include the ECRI Institute and the Tufts-New England Medical Center’s Cost-Effectiveness Analysis Registry.

In addition, private health plans conduct their own reviews of technologies and may or may not publicize results. An example of a more public and collaborative effort is the HMO Research Network, a consortium of more than a dozen health maintenance organizations that share findings and, in some cases, pool data for analysis.

CER in Practice: Around the Globe

CER bodies have emerged around the globe over the past decade. In the U.K., the National Institute for Clinical Effectiveness assesses cost effectiveness and makes coverage recommendations for the National Health Service (NHS). Australia, Canada, France and Germany have similar entities. Several middle-income countries are also undertaking evidence reviews including Brazil, Russia and Turkey.

Both Canada and the U.K. are also funding the prospective collection of comparative outcomes. In Canada, the Ontario Health Technology Advisory Committee funds field research networks that conduct studies on technologies where evidence is lacking. The NHS in Britain is prospectively collecting patient-reported outcome measures for elective surgeries in orthopaedics. Post-operative scores and complication rates are posted monthly online.10

In addition to these studies, comparative outcomes are also available from the Australian, Swedish total joint registries and from the multi-national spine registry, Spine Tango.11,12,13

Looking Toward the Future

The voluminous comparative outcomes data coming from international sources described herein, combined with the significant funding of CER at the Federal level to the tune of over $1.3 billion over the next few years, will lead to a dramatic rise in the profile of CER and its impact on decision-making.

- The sheer volume of CER research emerging will change the balance of research in orthopaedics. Privately funded research (generally commercially driven) has predominated. The new CER projects will add a significant counterweight of publicly-funded data comparing treatments and products.

- Educational communications created by commercial entities for physician and patient consumption will need to address any opposing or differing perspectives generated by CER.

Adapting to a New Environment

At first blush, the impact of CER appears to favor more resource-rich companies. They can afford a more prolonged approval/adoption phase, and can underwrite longer term, more expensive studies on their technologies. However, the number of CER data emerging from publicly funded sources will level the playing field by producing comparative assessments that are independent of a company’s ability to fund research activity.

Companies need to be strategic in how they track and respond to the coming flood of comparative data. Recommendations include the following approaches.

- Obtain and read the available reports. The AHRQ and IOM websites list grant recipients that can be searched by clinical area. Keep abreast of Federally-funded CER projects in your field. Follow results of the Washington Health Technology Assessments.

- If you are in the arthroplasty business, read the annual reports from Australia, Britain and Sweden.

- In spine, follow reports from the Spine Tango registry and stay abreast of any further action from the Coalition on Lumbar Fusion.

- Identify the evidence gaps in yours and in your competition’s technologies. Understand the benchmarks you will need to meet in terms of efficacy and cost to stay competitive in this data-driven environment. Choose study endpoints carefully so that they can be compared with other studies in the literature. Think of data as an insurance policy against the potential impact of CER. In the era of CER, data collection will be mandatory. Data takes time to mature, so start collecting it now in order for it to be available when you need it.

- Orthopaedic surgeons should consider the advice of the Washington State Orthopaedic Association, which recommends that members use both a disease-specific and a general health outcomes instrument in their practice, and measure these outcomes in all their patients on a regular basis.

Having the data to show that your technology or procedure provides measurable benefits at reasonable costs is the only way to stay afloat on the flood of CER data currently available to healthcare decision-makers.

REFERENCES

1. Spinemarket, Inc. (www.spine-market.com)

2. Orthopedic Network News (www.orthopedicnetworknews.com)

3. Orthopedic Network News

4. Research on the Comparative Effectiveness of Medical Treatments: Issues and Options for an Expanded Federal Role. The Congress of the United States, Congressional Budget Office, December 2007.

5. Pearson SD and Bach PB. “How Medicare Could Use Comparative Effectiveness Research In Deciding On New Coverage And Reimbursement,” Health Affairs 29, No.10(2010):1796-1804.

6. Milligan C. “Reshaping Medicaid (Discussion Draft),” National Governors Association.

7. Medicaid Spending Growth and Options for Controlling Costs. U.S. Senate Committee on Aging, July 2006.

8. Health Technology Assessment, Washington State Health Care Authority.

9. Franklin GM and Budenholzer BR. “Implementing Evidence-Based Health Policy in Washington State,“ NEJM October 29, 2009, Vol. 361 No. 18:1722-1725.

10. Patient Reported Outcome Measures (PROMs) Monthly Summary. Health and Social Care Information Centre.

11. National Joint Replacement Registry, Australian Orthopaedic Association.

12. Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register

13. Spine Tango, EuroSpine

Dr. Sledge, M.D., MPH, is a founder of Strata, a medical informatics company that offers software solutions to collect, analyze and disseminate evidence about established and emerging technologies. Strata has over 12 years of experience with patient data registries and decision support tools.

Dr. Sledge received her medical degree from University of Maryland School of Medicine and holds a Masters in Public Health degree from the Harvard School of Public Health. S