Profit as a percentage of sales is an almost universal measure of product or customer value. When someone says, “We earn a ten percent profit on our sale of Product X,” it means that every time they sell $1.00 of Product X, they pocket a $.10 profit. It is taken for granted that the ten percent profit realized on Product X makes it more valuable to an organization than the eight percent profit realized on Product Y. Unfortunately, this common measurement—profit as a percentage of sales—is about as good a tool for measuring the value of a product or customer to an organization as a thermometer for determining a wind-chill index. It only provides one-half of the information needed to make an accurate measurement of value.

The purpose of a for-profit company is not to generate the highest possible profit as a percentage of sales. Its purpose is to provide the best possible return on the owner’s investment. Calculating profit as a percentage of sales requires two numbers: profit and sales. Calculating return on investment also requires two numbers: profit and investment. It is impossible to determine the contribution of an individual product or customer to the attainment of the company’s overall financial objective without attributing, either directly or indirectly, both profit and investment to that product or customer.

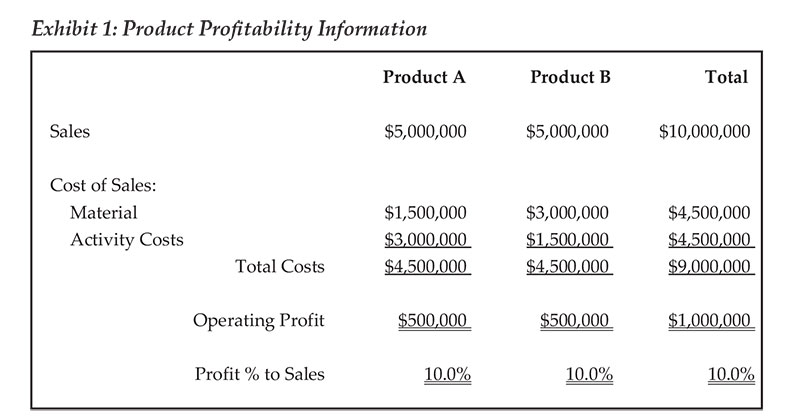

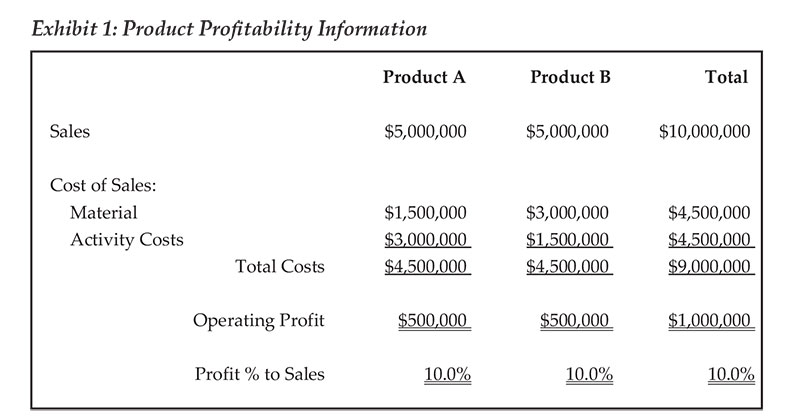

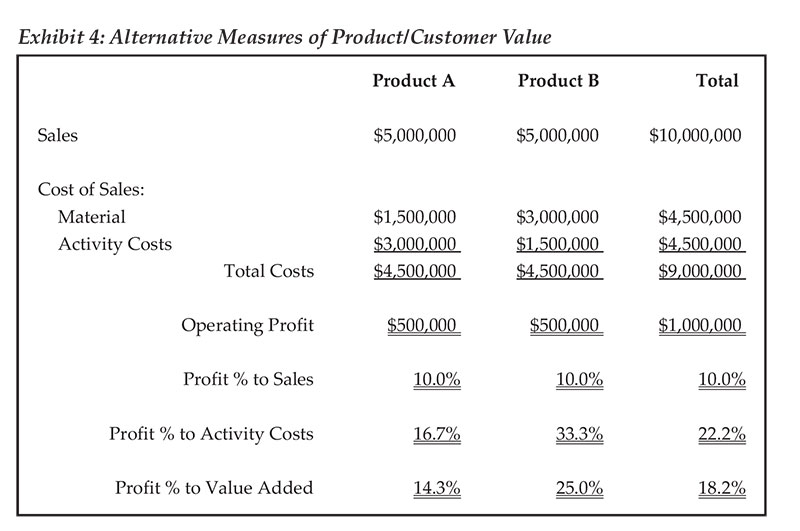

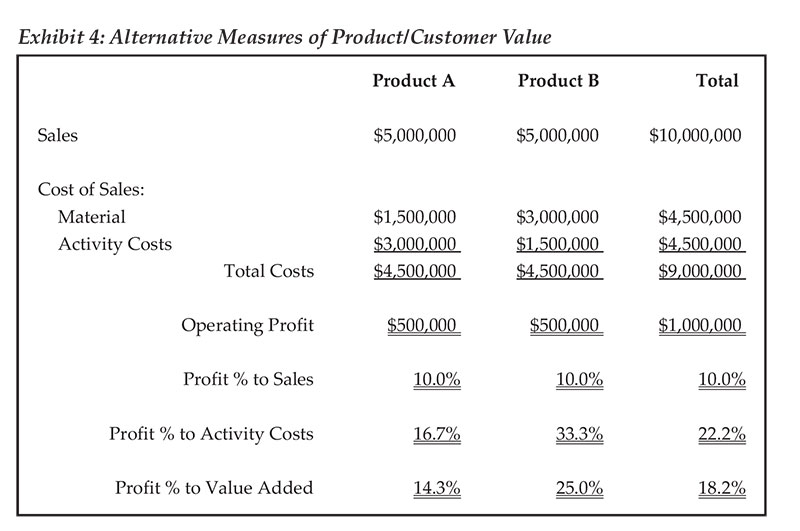

Consider the company whose product profitability information is shown in Exhibit 1. The company has two products: Product A and Product B. Both products generate $5 million in sales, and the total cost of both products is $4.5 million. As a consequence, the profit as a percentage of sales for both Product A and Product B is ten percent.

Is the value—and therefore the desirability—of these two products really equal? Consider this, as measured by activity cost (the cost of operating the business: salaries, wages, benefits, taxes, depreciation, utilities, consumables, etc.) twice as much cost is required to generate Product A’s profit than is required to generate the equivalent profit selling Product B ($3 million vs. $1.5 million). Since twice as much cost is required, it could be inferred that the resources required to produce $1 of Product A sales are twice those required for $1 of Product B sales. In effect, the company can produce $2 worth of Product B and a $.20 profit using the same resources it takes to produce $1 of Product A and a $.10 profit.

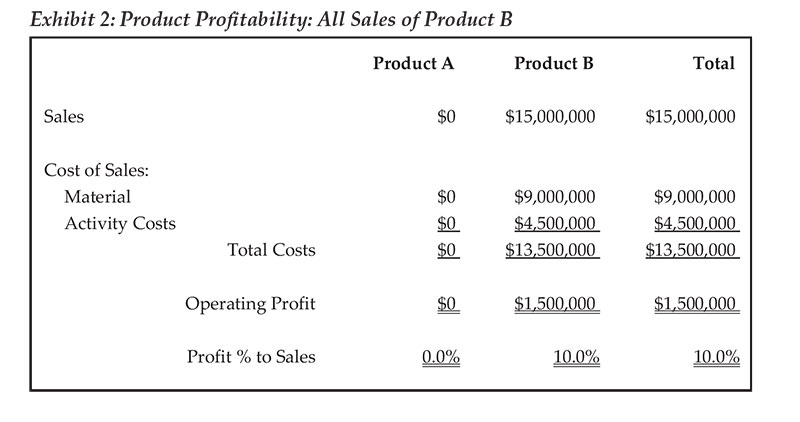

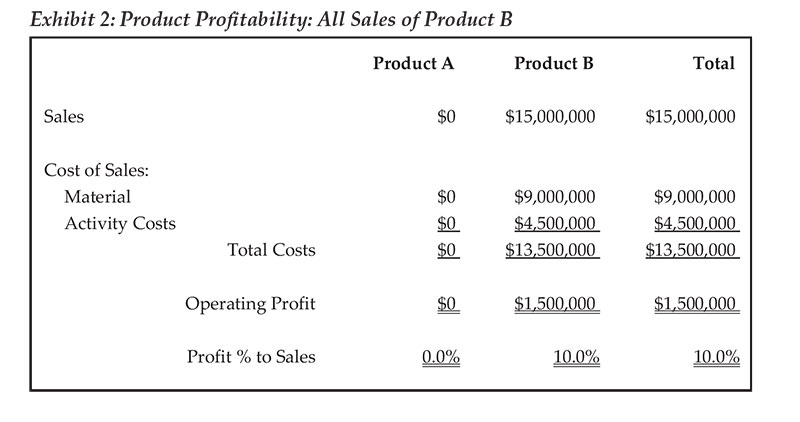

If the $4.5 million of activity costs represents the company’s capacity, it could generate $15 million in sales and $1.5 million in profit if all of its products were like Product B (See Exhibit 2.), but could only generate $7.5 million in sales and $750,000 in profit it they were all like Product A. (See Exhibit 3.) The existing capacity is only capable of generating half of its potential profit with items like Product A. Does this sound like Products A and B are of equal value in helping the company reach its financial objectives?

As a first step in evaluating an individual product’s or customer’s value to a company, it might be better to measure profit as a percentage of the product’s or customer’s activity costs as an indirect, or surrogate, measure of investment. As shown in Exhibit 4 on page 46, Product B’s profit as a percentage of activity cost is twice that of Product A, indicating that it is twice as valuable—an evaluation supported by the “all Product B vs. all Product A” comparisons in Exhibits 2 and 3. Although by no means a perfect measure, profit as a percentage of activity cost is certainly a much more representative measure of the two products’ value to the company than the traditional measure of profit as a percentage of sales. Making this simple change alone will improve a company’s ability to pick and choose among the business opportunities available in the marketplace.

An alternative indirect measurement of product or customer value—also shown in Exhibit 4—is profit as a percentage of value added. Value added can be measured by subtracting the cost of direct purchased materials, components and service from sales. It represents the value the company has added to the goods and services provided by its vendors. It’s what for-profit organizations do for a living—use their resources to turn purchased inputs into outputs of greater value.

When compared using this measure, Product B again comes out substantially ahead of Product A.

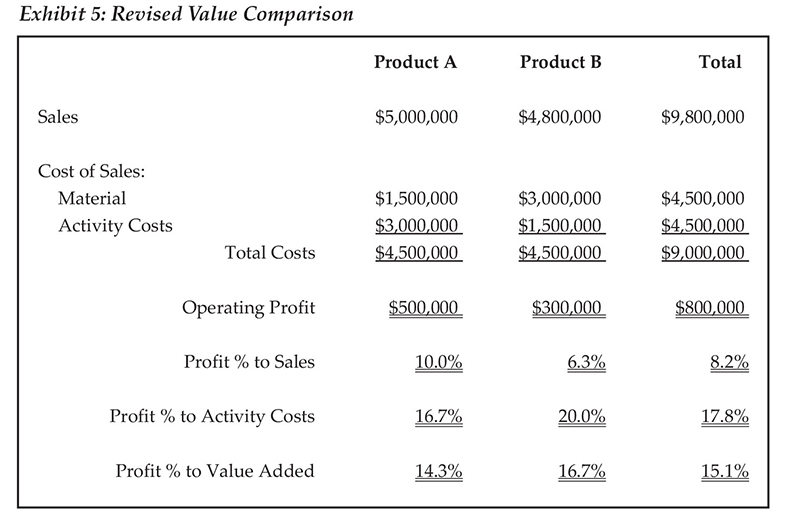

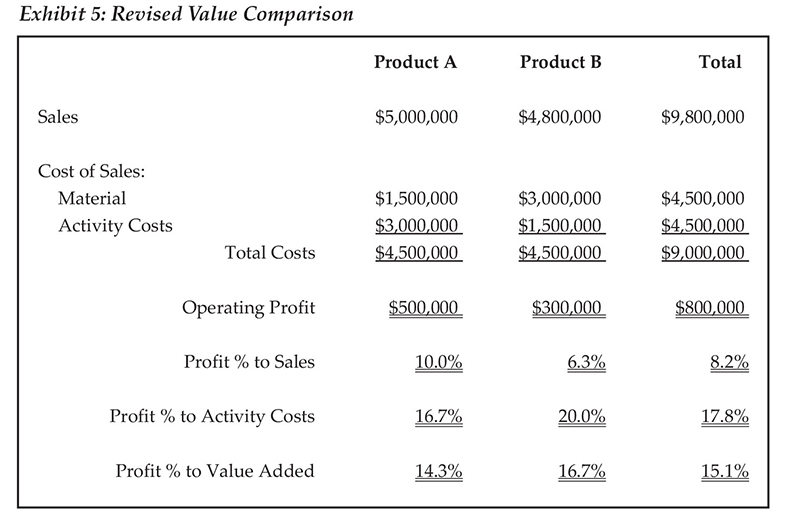

But what if Product B’s traditional measure—profit as a percentage of sales—is significantly less than Product A’s? Will Product A then emerge as the preferable product? Exhibit 5 on the following page shows a situation wherein Product B has only a 6.3 percent profit percentage to sales as compared to Product A’s ten percent.

As shown in Exhibit 5, Product B is still the more valuable product despite a profit as a percentage of sales measure that is 3.7 percentage points lower than Product A’s. Both of its alternative measures—profit as a percentage of activity costs and profit as a percentage of value added—are superior to Product A’s. A repeat of the “all Product A vs. all Product B” analysis performed in Exhibits 2 and 3 bears this out. Even with its lower profit as a percentage of sales, an “all Product B” scenario generates a profit of $900,000, $150,000 greater than an “all Product A” scenario.

Although both “profit as a percentage of activity costs” and “profit as a percentage of value added” are indirect ways of incorporating investment into the determination of product or customer value, they are both superior to the “profit as a percentage of sales” measure that predominates business. Fortunately, both can be easily incorporated into an organization’s performance measurement system; the data is already there to make the calculations. Both remain, however, only surrogates for the direct attribution of investment to products and customers—a slightly more complex process that I will cover in Part II of this series.

Please note—a key assumption underlying this example is that the activity costs are an accurate measure of the work required. This means they cannot be based on an invalid cost model of the company, nor can they only include those costs Generally Accepted Accounting Principles allows for valuing inventory. All activity costs must be included, not just those required to value inventory and determine cost of goods sold. For purposes of our argument in the articles in this two-part series, we will assume that our example companies have measured activity costs accurately.

During more than 25 years as a consultant, Doug Hicks has championed the development of practical, down-to-earth cost management solutions for small and mid-sized organizations. In that time, he has helped nearly 200 organizations transform their history-oriented accounting data into customized, value-enhancing decision support information that provides accurate and relevant intelligence needed to thrive and grow in a competitive world. He shares his experience through seminars conducted throughout the U.S., in trade and professional periodicals and two books, including I May Be Wrong, But I Doubt It: How Accounting Information Undermines Profitability.