“Money already spent is a ‘sunk cost,’ and it is utterly irrelevant to decision making.” – Shlomo Maital

“Sunk costs are irrelevant” is a principle stated in Shlomo Maital’s book Executive Economics and in almost every book on decision making ever written. Despite this well-accepted principle of decision science, most companies continue to include their biggest sunk cost as a major factor in determining product and process costs as well as in other decision making situations. That cost is depreciation expense.

A capital-intensive company’s greatest sunk cost is the money it has invested in its productive capacity. Instead of ignoring this irrelevant cost, however, these companies “pick a life” from the list of allowable asset lives, “pick a method” from the list of acceptable depreciation methods, calculate a depreciation expense and then treat the expense as if it is both an accurate and relevant measure of cost.

The fact is, once it has been purchased, the amount paid for a capital asset is irrelevant. Up to the point of its purchase – before the cost becomes “sunk” – the purchase cost is not only relevant, but critical. The benefits to be gained should be sufficient to provide an adequate return on the funds being invested. Once purchased, however, the amount paid no longer matters. What does matter is how the asset can best be used to generate cash flow for the organization.

There are two ways a capital asset can generate cash for a business organization: it can be sold or it can be used. The value received by selling an asset depends on its market value – not its original cost. The value received by using an asset depends on its money making capability – not its original cost. The asset’s original cost is irrelevant in both cases. So why do companies insist on taking the purchase cost, processing it through a depreciation schedule and assigning it to products and services?

The answer is simple. Accountants – the historians of the business – make them do it. These well-meaning scribes of history, who always keep a sharp lookout in the rear view mirror, want to monitor where the company has been – how good were its decisions. Their objective is not to look through the windshield and provide information to ensure the quality of future decisions. Management, however, needs a clear vision of where it is going. Only by looking forward can management make sure the company is headed towards a successful future. Managers cannot afford to incorporate irrelevant, sunk costs in their decision making processes. Instead they must look forward to future, relevant costs.

The Capital Preservation Allowance

As a company sells its products and services, it must not only generate a return on the owners’ investment, it must also generate the funds necessary to preserve its current productive capabilities. The funds generated from selling today’s products and services should not be viewed as paying for yesterday’s capital outlays; instead, they must be viewed as generating the funds for a critical category of future capital outlays – those necessary to preserve the company’s existing capital base.

In the past, most business executives assumed that by including depreciation expense in product and service cost, they were providing for these future expenditures. But the calculation of depreciation expense has nothing to do with the future – it focuses entirely on past actions! Companies with older assets are probably understating the need for capital funds to simply keep them in business. Companies with newer assets may be providing for more capital than will be needed and, as a result, may be quoting prices that put them into an uncompetitive position.

One answer is for management to look through the windshield – not the rear view mirror – and develop a Capital Preservation Allowance (CPA). This allowance is a forward-looking view of capital requirements that replaces depreciation in the calculation of product and process cost and enables a company to effectively accumulate the funding required from current products and services to preserve existing productive capabilities.

Depending on the situation, the CPA can be simple or complex. A company whose capital assets form a single, homogeneous system that is used to produce nearly all of its products or generate all of its services may only need a single, company-wide CPA for all of its future capital requirements. A company with several lines of business, each with different levels of future capital needs, may need multiple CPAs – one for each line of business. At more complex organizations, where different asset types have different future capital needs, a different CPA may be needed for each type of asset. Regardless of the situation, however, the CPA must look to the future, not the past.

The mechanics of a CPA are not complex. In principle, it is like establishing a “sinking fund” to provide for future capital outlays. The process should begin by forecasting necessary capital outlays for a representative number of years. For CPA purposes, capital outlays mean principal payments on existing and future loans used to finance capital purchases, any capital assets purchased for cash and lease payments. Keep in mind that we’re funding the preservation of capital assets over time, not trying to match each individual year’s funding level with that year’s expenditures.

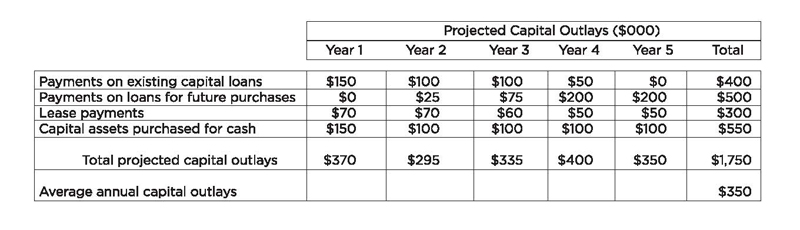

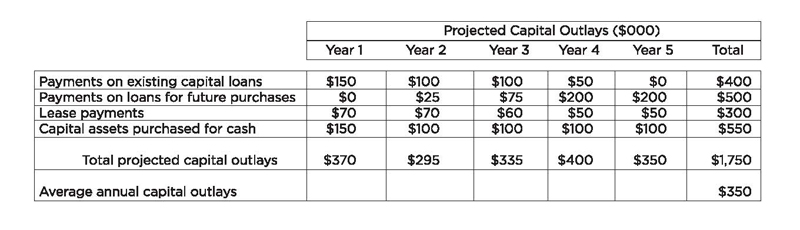

For example, based on its current forecast of business, one company anticipates the following expenditures to preserve its existing production capabilities over the next five years. This is illustrated in Exhibit 1.

Exhibit 1: Projected Capital Outlays for Asset Preservation

The simplest way to incorporate this $350,000 average annual amount into the company’s cost structure is to establish a $350,000 CPA and add it to product or service cost as a percentage of conversion or activity costs. On the other hand, it could also be separated into activity or cost centers and flow through them into costing rates in the same manner as depreciation expense. One major shortcoming of these approaches, however, is that they assume that the need to replace assets is based on chronological time, not usage.

Is The Funding of Future Capital Outlays a Fixed Annual Cost?

Depreciation expense is accounted for almost exclusively as a fixed cost. An asset’s depreciable base is determined, an appropriate life selected and one of the approved methods chosen. An annual provision of depreciation is then calculated and treated as a fixed or period cost during the asset’s depreciable life. This provision may vary each year of the asset’s life, but during each of the earth’s orbits around the sun, it is considered fixed.

The fundamental underlying assumption behind this method of recording depreciation is that chronological time is depreciation’s driver. A production asset is assumed to depreciate the same amount when it is used for 1,000 hours during a year as when it is used for 6,000 hours because time, not use, is used as the cost’s driver. This may be true for assets that become obsolete before they wear out – like many high-tech, non-production capital assets – but it does not hold true for a vast majority of the capital assets used in manufacturing. Despite this mismatch between reality and accounting practice, the treatment of depreciation expense as an annual fixed cost continues to be followed blindly resulting in many decisions that are at variance with economic reality.

During my four decades in industry, I’ve seen many companies take on disastrous incremental jobs because they “had to cover the year’s depreciation expense,” over-cost (and therefore over-price) products because they were in the early, high-depreciation years after making major capital expenditures, “run the heck” out of equipment to get the fixed depreciation cost per piece a low as possible during a given fiscal year, or severely under-price products because their accounting records showed little or no depreciation expense – all because they believed in the misleading illusion of depreciation expense.

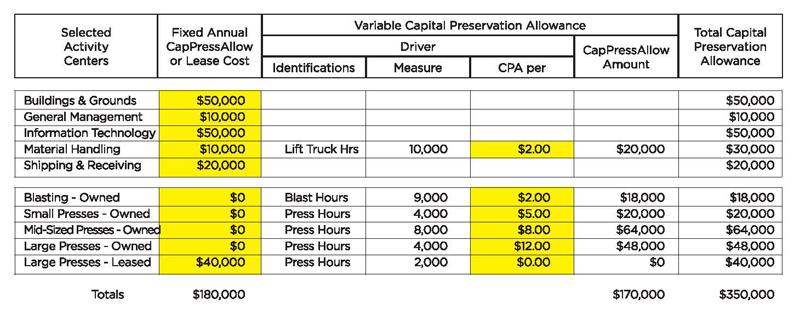

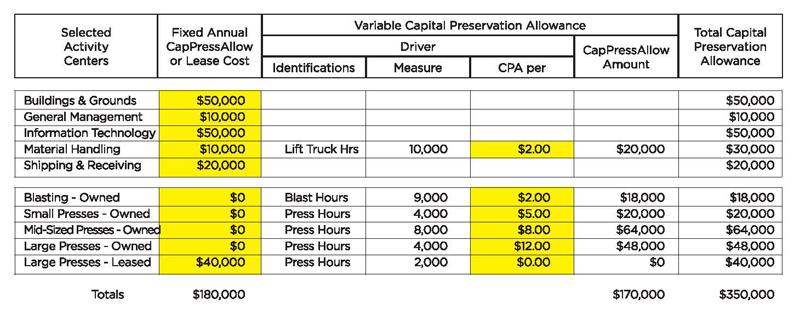

A more appropriate approach would be to separate CPAs for an organization’s various activities into two categories: those driven by time and those driven by usage. Those driven by time would be treated like depreciation – as a fixed annual cost. Those driven by usage would be linked to a driver that represents that usage. Exhibit 2 shows the breakdown of our example company’s CPA.

In this example, it is assumed that most non-production assets are either leased (company vehicles, lift trucks), will become obsolete before they wear out (information technology) or do actually wear down over time (building). The CPA for each of these is treated as a fixed annual amount. There is, however, one exception among these non-production assets: several lift trucks are owned. The need to replace these assets will accrue as they are used. As a result, a provision of $2.00 for each hour these company-owned lift trucks are in use is established to provide for their eventual replacement.

Exhibit 2: Dual-Driver Capital Preservation Allowance

All but one of the company’s production assets are company-owned and will likely need replacement after being used a certain number of hours, not the number of years owned. After carefully evaluating the likely life of each asset, how they will eventually be replaced and the cost of those replacement assets, a “CPA per hour of use” is established for each asset category. One production asset – a large press – is leased. There will be a $40,000 annual outlay for this asset, whether it is used for 10 hours or 4,000 hours. As a consequence, it will be assigned a time-driven CPA of $40,000 per year.

The result, based on the company’s planned level of business for the coming year, is a CPA of $350,000: $180,000 time-driven and $170,000 usage-driven. Have a look at Exhibit 3.

Exhibit 3: Dual-Driver Capital Preservation Allowance @ 70% of Plan

But what if the year doesn’t turn out as planned and the actual level of business is only 70% of what the company had anticipated? If the CPA was 100% time-driven, as is the case with depreciation expense, the cost would remain $350,000. Since, however, those assets whose need for replacement is usage-driven have been given a “per hour” rate, not a “per annum” rate by the company, its annual CPA cost is reduced to a more representative $299,000, as shown in Exhibit 3. Had actual levels been at 130% of plan, the CPA would have increased to $401,000 – again a more representative amount, because the need to replace a significant portion of the company’s capital assets is driven by their usage, not the fact that the earth orbits the sun once.

Conclusion

There are, undoubtedly, approaches other than GAAP-based depreciation expense that can be developed to more closely reflect economic reality. The key lesson to be learned is that GAAP-based depreciation expense is a misleading illusion and should never be used in any forward-looking cost calculation intended to support management decisions. It fails to mirror economic reality because 1) it is based on the original (sunk) cost of a capital asset (which is irrelevant) and 2) it assumes chronological time drives the need to replace equipment.

Keep in mind that the Capital Preservation Allowance is intended to cover the preservation of existing capabilities, not the expansion of those capabilities. Capital expenditures made to support growth are funded by the profits generated by the sale of current products and services; they are not a cost attributable them. The CPA does not replace depreciation expense for tax or GAAP accounting purposes. It is intended to accurately reflect the fundamental economics that underlie a company’s operations and improve the quality of business decisions. Neither tax accounting nor GAAP accounting reflect economic reality; they reflect tax or GAAP “one-size-fits-none” rule compliance. A company can handle tax and book depreciation expense however it wants to minimize tax liabilities or maximize reported profits. If it uses it for decision making, however, it will be relying on economic illusions, not economic facts and the quality of its business decisions (and bottom line) will suffer accordingly.

During more than 25 years as a consultant, Doug Hicks has championed the development of practical, down-to-earth cost management solutions for small and mid-sized organizations. In that time he has helped nearly 200 organizations of all kinds transform their history-oriented accounting data into customized, value-enhancing decision support information that provides accurate and relevant intelligence needed to thrive and grow in a competitive world. He shares his experience through seminars conducted throughout the U.S. and in trade and professional periodicals (including Management Accounting, Cost Management, Manufacturing Engineering and Journal of Accountancy) and two books, including I May Be Wrong, But I Doubt It: How Accounting Information Undermines Profitability. He can be reached at