As we begin the second decade of the 21st Century – over a quarter-century into the “cost measurement and management revolution” – most U. S. manufacturers, including those who precision manufacture orthopaedic devices, continue to base not only their day-to-day cost accounting systems, but also the cost information they use to support critical management decisions, on cost models driven primarily by direct labor. These cost models, developed at a time when product and process variety were minimal and direct labor was a major cost of manufacturing, are simple, easy to use and explain, compatible with most enterprise resource planning (ERP) and other manufacturing software and, in a vast majority of cases, totally inappropriate.

The introduction of high-tech and computer-controlled manufacturing processes, the ever-increasing demand for complexity and variety in manufactured products, the adoption of lean manufacturing philosophies and the expansion of pre- and post-manufacturing services – including distribution and fulfillment – have pushed the realities of 21st Century manufacturing far beyond the capabilities of “simple and easy to use.” As costing pioneer Alexander Hamilton Church stated over 100 years ago, “No facts that are in themselves complex can be represented in fewer elements than they naturally possess…there is a minimum of possible simplicity that cannot be further reduced without destroying the value of the whole fabric.”

In the 21st Century, direct labor-based costing has fallen far below the “minimum of possible simplicity.” It no longer provides a valid model of the economics that underlie a modern orthopaedic device manufacturing organization and, as a consequence, should no longer be relied upon as a method of measuring a manufacturer’s product, process or customer costs – especially when these costs are used to support critical management decisions.

What’s Wrong With Direct Labor-Based Cost Models?

In its simplest form, a manufacturer will use a single, plant-wide overhead rate – expressed as either a percentage of direct labor cost or an overhead cost per direct labor hour – to be added to direct labor’s hourly cost. All non-manufacturing costs will then be assigned to cost objectives (products, customers, etc.) as an add-on percentage (known commonly as an SG&A rate). The irrationality of such a cost model should be apparent to anyone who gives it a second thought.

Is the cost of an individual manually assembling or visually inspecting a part the same as one who operates a high-tech machine center that devours power and expensive perishable tooling? If a worker can operate two machines at the same time, does each machine only cost one-half as much as when a worker can only operate one machine at a time? Is the cost of heat treating or plating determined by the amount of time it takes for workers to load and unload parts? A direct labor-based cost model with a single, plant-wide overhead rate suggests that the answer to each of these questions is “YES” – an answer that totally defies logic.

Many accountants believe that if they segregate manufacturing into multiple cost centers and then develop separate direct labor-based overhead rates for each cost center, the problem will be averted. That is, unfortunately, not the case. A company using multiple direct labor-based overhead rates to apply indirect manufacturing costs and a traditional, company-wide, total-cost based SG&A rate to assign non-manufacturing costs to products and customers will continue to experience shortcomings, such as:

- The cost of cells and lines will be misstated and, as a consequence, any products manufactured using these cells and lines will be costed inaccurately. Cells and lines require a fixed amount of cost to operate, regardless of how many workers are present. Occupancy and capital equipment costs are primary examples. The variable costs of operating cells and lines (utilities, perishable tooling and other consumables) are generally driven by the operation of the equipment, not the activity of a worker. Linking such fixed and variable costs to the hours worked by cell/line workers makes it appear as if these costs vary in direct proportion to those hours. A smaller crew attending the line implies that these costs are reduced, when in reality they stay the same. A larger crew will imply that these costs increase when, in fact, they remain the same. The ramifications of this error are many, from industrial engineers miscalculating the impact of direct labor savings, to losing profitable products due to overpricing, or winning unprofitable jobs due to underpricing.

- CNC and any other equipment that requires only a partial direct worker, or perhaps no worker at all, will be costed incorrectly. If a worker attends two machines, each machine’s operation will still appear to cost only one-half as much as it does when the worker attends a single machine. Obviously, this does not reflect reality. The equipment cost does not vary with the hours of direct labor; it varies with the equipment’s hours of operation. The impact on pricing decisions should be readily apparent. The misstated savings from labor reductions or the impact of adding workers to improve equipment throughput time will also mislead management.

- Any equipment whose attending crew size can vary based on the characteristics of the product being produced will be costed incorrectly. As in the case of fractional workers, the equipment does not cost twice as much to operate simply because it requires two workers instead of one, nor does it cost one-half as much when one worker is required as opposed to two. The pricing and cost savings implications are the same as with CNC equipment.

- The price paid for purchased materials, components and outside manufacturing services will appear to be the total cost of those items. The cost of purchasing, handling, quality, storing, financing and other administrative activities required to support purchased (or customer provided) materials, components and outside manufacturing services will be buried in manufacturing overhead or SG&A costs. The minimal support cost for off-the-shelf items will go unnoticed, as will the much higher support cost of custom items. Slow-turning items will not be penalized for the extra space and financing they require, while the benefits of fast-turning items will be invisible. No cost will be assigned to customer-provided or consigned items, even though they require support from many of the same activities as the company’s purchased items. The major costs needed to support outside manufacturing services, including the extra inventory-related costs when items are sent outside in the midst of the manufacturing process, will be ignored. The cost benefits of high-volume items purchased in bulk and handled using mechanized systems will be lost, while the extra cost required to support low-volume items requiring substantial handling and storage will be ignored. Perhaps most dramatic will be the total absence of support costs related to the purchase of items from overseas. Offshoring decisions will be made in total ignorance of the economics that underlie such a critical decision.

- Post-manufacturing costs, like those related to finished goods storage, order picking, order processing, shipment preparation and logistics, will be invisible. Because the costs of these activities lie buried in manufacturing overhead or the company’s SG&A rate, it is impossible to assign them to the customers that require them, thereby making accurate measures of customer profitability impossible. Instead, these costs will remain buried in manufacturing overhead or SG&A and be spread like peanut butter to all customers in proportion to their product costs.

These are just a few common shortcomings inherent in direct labor-based costing at manufacturing firms. There are many others. Each manufacturer will have its own unique set of issues. Nevertheless, even with “band aids” applied to a direct labor-based cost model, the high-quality product, customer and process cost information necessary for a manufacturer to make sound decisions and take effective actions will be non-existent. Instead, cost information will remain inaccurate and misleading.

What Difference does it Really Make?

If the negative impact isn’t obvious of the distortions that direct labor-based costing have on a manufacturer’s decision making, understanding the effect they have on pricing decisions should make the connection crystal clear. There is a law of economics – known at my firm as Hicks’ First Law of Pricing – that applies here. That law goes like this: “A company will get a lot of business when it does not charge its customers for things it does for them, but it will not get much business when it attempts to charge its customers for things that it doesn’t do for them.”

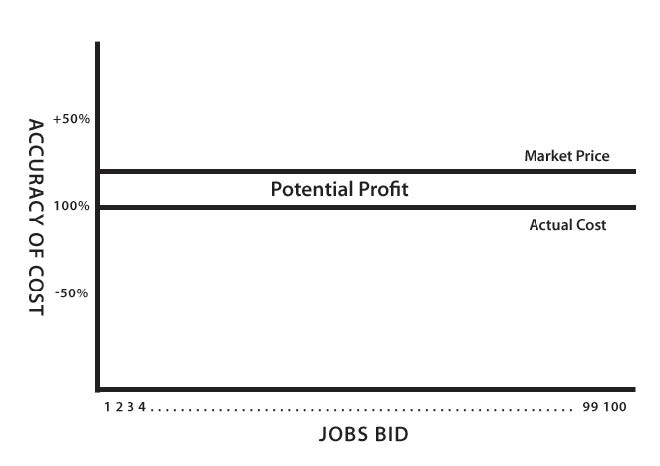

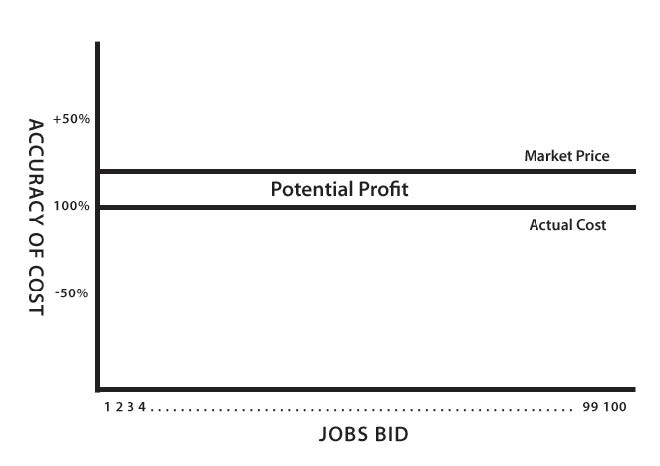

For example, one manufacturer has overall productivity that is about average for its industry and marketplace. Under normal economic conditions, the market will allow this company, whose costs are at the industry average, to charge a price that will enable it to recapture its cost and earn enough of a profit to ensure its continuing ability to supply the marketplace. If this company accurately calculates its “fully-absorbed” costs and adds a market-supportable profit margin on each of one hundred possible contracts, it should be competitive on those contracts and will earn its expected profit margin on any contract it is awarded.

This situation is shown graphically in Exhibit 1 in which the horizontal axis represents one hundred contracts bid and the vertical axis the percentage accuracy of its fully-absorbed cost estimates. The market prices shown provide consistent margins above the accurately determined costs. The area between the market price and the 100% accurate contract costs represents the profit on any contract awarded at the market price.

|

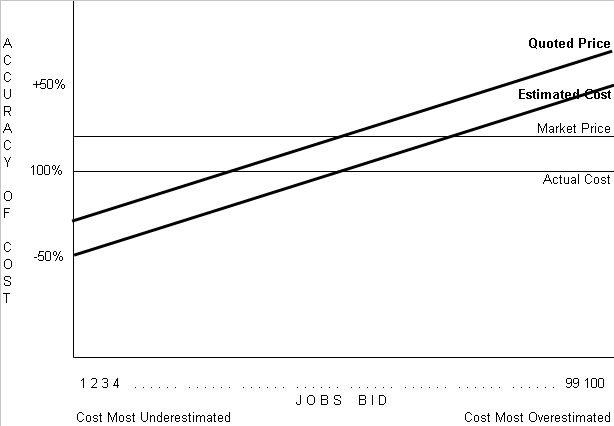

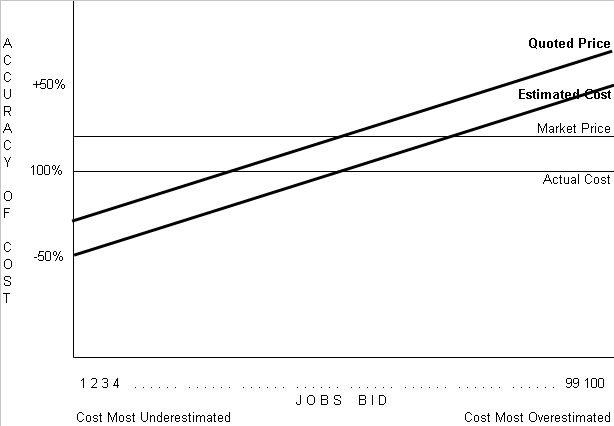

If this company uses an inappropriate, over-generalized methodology (such as applying overhead costs on the basis of direct labor hours/dollars) to estimate its costs, it will overestimate the fully-absorbed cost on approximately one half of the contracts bid and underestimate the costs on the other half. As a result, it will establish an acceptable price (quoted price) at levels that will be under the market for those contracts whose costs were underestimated and over the market for those contracts whose cost were overestimated. This situation can be seen graphically in Exhibit 2 in which contracts are sequenced from left to right, starting with the contract whose cost was most underestimated and ending with the contract whose cost was most overestimated.

|

Looking at Quoted Price and Market Price, it is obvious that the company will be much more likely to be awarded contracts on the left side of the diagram – contracts bid at less than market price – for which it was “not charging the customer for things it does for them.” Conversely, it will not be awarded contracts on the right side of the diagram – contracts that could have been profitable at much lower prices – for which it was “charging the customer for things it does not do for them.” Unfortunately, actual costs do not care whether they have been over or underestimated; they will be actual either way. As Exhibit 3 clearly shows, if the company is awarded those contracts that were inadvertently priced below market, it has little or no change of financial success. At the same time it will be missing out on the potential profits that could have been earned at the market price on those contracts its inaccurate costing methodologies caused it to overprice.

|

Pricing is not the only area where distortions and problems lead to low-quality decisions. The savings from operating improvements are regularly miscalculated. One company added new controls to a piece of equipment that made it possible to reduce the number of workers needed to operate the machine from two to one. The anticipated cost reduction not only included the cost of one laborer, but it was estimated that the equipment’s variable operating costs – including perishable tooling and utilities – would also cut in half. The latter was not a savings they were likely to realize.

Another major area where direct labor-based costing adversely impacts a manufacturer’s decision making lies is in insourcing and outsourcing decisions, particularly those related to offshoring. Chasing the lowest “price” for a purchased item does not always insure that the lowest “cost” will be obtained. I know of one company that saved $3 million annually in component prices by moving the manufacture of a group of parts to China. The only catch was that they spent $3.5 million annually – all of which was buried in its manufacturing overhead and SG&A costs – to achieve this savings. It’s no wonder this company was out of business less than two years later.

The inability to link customer-related costs to the customers that require them also leads to poor pricing decisions and inaccurate measures of customer profitability. Consider the case of a manufacturer that sells the same product to two different customers at the same price. They produce 10,000 units in a single batch each week. Five thousand units are immediately shipped to one of the customers. The remaining 5,000 units are moved to finished goods inventory, with 1,000 units shipped to the customer each day. Do you suppose each of these customers generates the same amount of profit for the manufacturer? The company’s direct labor-based costing model makes them appear equal in profitability.

Decision Cost Information ≠ Cost Accounting Information

One of the great philosophical mistakes in cost measurement and management is the belief that cost information for decision making must come from a company’s cost accounting system. The purpose of cost information is insight—insight that will improve a company’s decision making processes and enhance its bottom line. Cost accounting systems are designed to value the company’s overall inventory and calculate its overall cost of goods sold for use in company-wide financial statements – not to determine the cost of the individual elements that comprise the company’s operation. As a consequence, cost accounting systems incorporate too many generalities and shortcuts to provide accurate and actionable cost information.

A manufacturer does not need a great cost accounting system to have high-quality cost information to support its decisions. It needs a valid economic cost model of its business. Fortunately, the creation of a valid cost model that provides accurate, actionable cost information requires only a fraction of the resources needed to implement a new cost accounting system. A fundamentally sound ERP or other manufacturing information system is still important – it provides much of the data necessary to populate the cost model – but it’s the model that generates accurate, relevant and actionable cost information, not the system. Many manufacturers have created and used valid cost models to enhance their bottom lines without changing their day-to-day cost accounting systems.

Conclusion

A 21st Century manufacturing firm that uses a direct labor-based cost model to determine costs support decisions is putting itself at considerable risk. Direct labor may have been an appropriate basis for developing cost information when competition was less, products were uniform, customers demanded few (if any) extra services and direct labor was the major factor in manufacturing. None of that is true today.

Today’s manufacturing environment requires high-quality cost information – information based on a valid economic cost model of the business – if the manufacturer is to thrive and grow in the future.

During more than 25 years as a consultant, Doug Hicks has championed the development of practical, down-to-earth cost management solutions for small and mid-sized organizations. In that time he has helped nearly 200 organizations of all kinds transform their history-oriented accounting data into customized, value-enhancing decision support information that provides accurate and relevant intelligence needed to thrive and grow in a competitive world. He shares his experience through seminars conducted throughout the U.S. and in trade and professional periodicals (including Management Accounting, Cost Management, Manufacturing Engineering and Journal of Accountancy) and two books, including I May Be Wrong, But I Doubt It: How Accounting Information Undermines Profitability.