Content sponsored by 3D Systems

In December 2017, FDA finalized its Additive Manufacturing Guidance, providing broad considerations for utilizing the technology for developing medical devices. Of course, as with most FDA guidance, gray areas remain. Orthopaedic professionals attending OMTEC 2018 were able to bring their pressing questions to FDA, as well as representatives from ASTM, DePuy Synthes and SME. Here we recap a handful of those questions and answers.

Based on your experience, what are some of the largest gaps you see with FDA submissions, whether it is verification and validation or something else?

David Hwang, Ph.D., Spinal Device Reviewer, Office of Device Evaluation, CDRH, FDA: It depends on whether it’s a new company with a new process or a company that comes in with a process that they’ve already had cleared. For a new company with a new process, the main thing that helps us is your process flow chart. It doesn’t have to go into details about what those processes are, but knowing what each step is and who is doing the step helps us understand where we can start with our questions.

When we ask, people have the information. Generally, organization is what helps us the most.

Dan Fritzinger, Manager, Global Instrument Innovation, DePuy Synthes: To reiterate one point that is particularly key for additive manufacturing, you should have a good process flow map of all of the steps involved. People tend to focus on the printing portion, but there are a number of steps upstream and a number of steps downstream.

Personally, I’ve taken a lot of value from mapping that out. The more detail you put into the map, the better, because it’s going to help when you’re writing your validation goals, figuring out what you have to verify, troubleshooting. It’s a really good process to map out your flow for additive.

What might companies neglect to include in their FDA submission?

Hwang: In terms of mechanical testing you need for a specific implant, usually bench testing is required. In addition to the normal questions, like what is your worst case size, worst case part, we typically ask: What is your worst case print? Does it have to do with reuse of powder, or are there different variables in your build plate that potentially produce a range of outcomes in your print process? That print should be used in your bench testing or your validation process.

Biocompatibility is another one. In the past, orthopaedics has gotten away with materials having a long history of use. When FDA reissued biocompatibility guidance (2016), that process alone now doesn’t get everyone where they need to go. Something that should be covered is the segment between your printing and the actual base material biocompatibility, and also the post-processing steps and why those processes don’t impact your end biocompatibility.

What’s the current thinking from an FDA and business perspective on use of dedicated equipment or dedicated factories for titanium-only vs. the other end of the spectrum: using a machine that employs multiple materials, but has a good cleaning procedure?

Hwang: We don’t recommend one or the other as long as you can demonstrate that your product is going to come out right. Anecdotally, I think that most people in their prototyping phase do change materials. But as far as I’ve heard, it’s been too much trouble and people usually dedicate one machine.

Fritzinger: It’s definitely a risk-based decision and something to address. The risk is contamination. If you can prove that you have cleaning procedures that work and you can validate them, more power to you. We don’t do that. We have dedicated machines for dedicated materials, because we don’t feel that we could prove that we can clean the machine out to where we’re comfortable that we’ve mitigated the risk. Our process is more expensive.

Carl K. Dekker, President of Met-L-Flo and Past Chairman of ASTM Committee F42: There aren’t closed loop systems where you can take out the entire feedstock and build chamber and interchange it with another one. If you’re going to do that, the probability of dedicating a machine to a material, setting it up, qualifying the builds and then continuing to run the same qualified builds on that equipment is going to be more effective and a lot higher probability of getting what you’re looking for, as opposed to hoping it was cleaned out properly.

Assume that you have two of the exact same part. One of them is created from a subtractive processes and the other from additive; your acceptance criteria doesn’t have to be equivalent, specifically, under fatigue. Do you have experience in reviewing applications where not all failures are critical failures? In this case, do you have different criteria than the predicate, which was manufactured in a CNC process?

Hwang: There isn’t a difference in what we accept in terms of failure of fatigue. The criteria for 3D printing for the device-specific testing you’re talking about is the same. I’m in the spine group. For fatigue failures, we don’t accept any failures, regardless of whether it’s functional or mechanical. Typically we look at run out for fatigue. Depending on the product, it might be five million cycles; we would compare that to a predicate that has a similar run out.

Fritzinger: It comes back to your design control plan. You created your user need and then your design inputs, determining that this is what this device has to do. At that point, you’re not considering which manufacturing method you’re using; you’re saying that this is what this device has to do. Then you make it, and have it tested to that.

Addressing the Standards Gaps

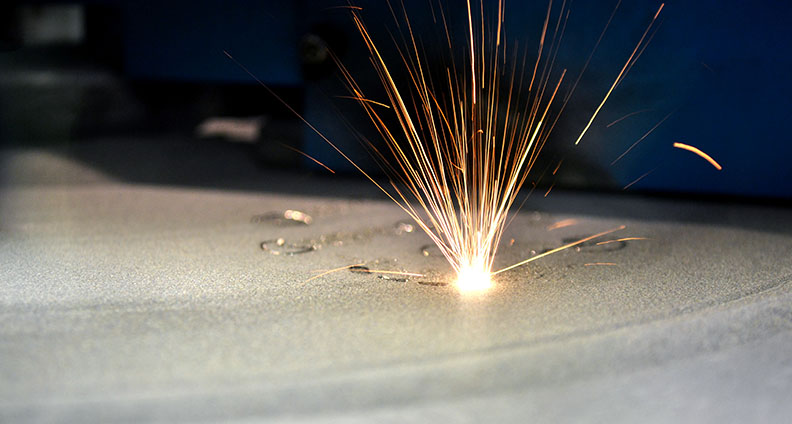

Numerous regulatory bodies, standards organizations, societies and device companies are investing in development of standards and specifications to employ additive manufacturing. While much of this is happening at an individual organization level, America Makes and American National Standards Institute established a collaboration, with representatives from the entities mentioned above, to create a roadmap that identifies existing and developing standards, assesses gaps and prioritizes recommendations for future standards. Version 2 of the roadmap was published in June, and we think you will find the 268-page report a helpful resource. The roadmap detailed 93 open standards and specifications gaps that organizations are working to close. Here, we recap three recommendations for gaps that were identified as high-priority.

Material Properties is mentioned throughout the identified gaps. Regarding finished material properties, the collaborative recommends standards are developed that identify the means to establish minimum mechanical properties (e.g., additive manufacturing procedure qualification requirements) for metals and polymers made by a given additive manufacturing system using a given set of additive manufacturing parameters for a given additive manufacturing build design. Developing standards will require generating data that currently doesn’t exist or is not in the public arena. Further, qualification requirements to establish minimum mechanical properties for parts need to be developed.

Recycle & Re-use of Materials has many practices dictated by materials companies. A concern is the effects of mixing reused and virgin material. The recommendation is to develop guidance as to how reused materials may be quantified and how their history should be tracked (e.g., number of re-uses).

Cleanliness of Medical Parts, including removing power residue, has no standardized protocol or acceptance criteria. The recommendation is to develop standard test methods, metrics and acceptance criteria to measure cleanliness of complex additive geometries that are based on existing standards, but focus on additive-specific considerations.

CL

Carolyn LaWell is ORTHOWORLD's Chief Content Officer. She joined ORTHOWORLD in 2012 to oversee its editorial and industry education. She previously served in editor roles at B2B magazines and newspapers.