Trauma is the third largest market segment by product sales in the global orthopaedic industry at 15 percent of the whole, trailing spine (18 percent) and joint replacement (34 percent), according to ORTHOWORLD® estimates. The segment stands to experience further growth as population numbers increase and people face age-related injuries.

According to surgeons and industry interviewed by BONEZONE, trends in trauma center on the rise in hip fractures, challenges of treating osteoporosis and pelvis fractures, the emergence and need for specialty plates and a place for biologics to enhance bone healing.

First, we present viewpoints from three orthopaedic trauma surgeons:

Eric E. Johnson, M.D., orthopaedic trauma surgeon at Ronald Reagan UCLA Medical Center

Heather A. Vallier, M.D., orthopaedic trauma surgeon at MetroHealth and member of the Orthopaedic Trauma

Association’s Board of Directors

Joel C. Williams, M.D., trauma specialist, Midwest Orthopaedics at Rush

BONEZONE: What trends do you see in products or procedures for the trauma market?

Johnson: The biggest thing in the last five years is osteoporotic fractures. Hospitals are overwhelmed with hip fractures. We see seven or eight times as many as we did 20 years ago. A lot of initiatives are addressing ways to maximize and treat these patients.

Johnson: The biggest thing in the last five years is osteoporotic fractures. Hospitals are overwhelmed with hip fractures. We see seven or eight times as many as we did 20 years ago. A lot of initiatives are addressing ways to maximize and treat these patients.

In the last ten years, I’ve noticed locking plate fixation technology. We can take care of osteoporotic fractures now much more easily, because these fixed implants don’t loosen. The bone can heal within the time that the plate is in place, so we don’t have failures.

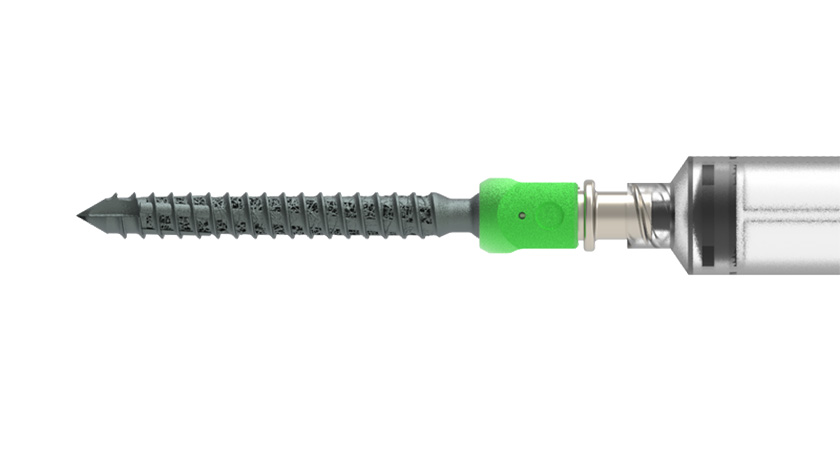

For osteoporotic fractures, especially in shoulder or tibia plateau fractures, screws can be cannulated, locked and have a blunt tip. You can put the screw into the system in a bad area of bone, as long as you don’t penetrate the opposite side into the joint. Then, you infuse a phosphate-type biomaterial through the screw that spreads out into the head and occupies space, so the screw doesn’t loosen. Hip fractures can be treated with more confidence that it’s not going to fall apart because you can fill the area around the implant inside the femoral head, giving more stability.

Vallier: There’s been a push toward specialty plate systems, as opposed to traditional plates which we would contour and modify ourselves. It’s challenging, because there are so many different plates out there now. You don’t necessarily need a specific plate for every area. Finding that balance of versatility of traditional implants, as opposed to having to add more trays and stock—whether it’s owned or consigned by hospitals—is a challenge.

Vallier: There’s been a push toward specialty plate systems, as opposed to traditional plates which we would contour and modify ourselves. It’s challenging, because there are so many different plates out there now. You don’t necessarily need a specific plate for every area. Finding that balance of versatility of traditional implants, as opposed to having to add more trays and stock—whether it’s owned or consigned by hospitals—is a challenge.

If you don’t keep all those things in your hospital, then when you have a distal humerus fracture [to treat], it’s a lot of running around for implant vendors to make sure things are processed out beforehand. People don’t plan to get hurt, so you can’t book it on the schedule two or three weeks ahead of time. For smaller hospitals it’s even more pressure to figure out how to have sets that are configured to treat a lot of body areas well without needing a lot of extra add-ons.

Some things that could be improved upon might be in the use of biologics. Bone and cartilage healing and repair are areas that are not currently met biologically. I see a lot of potential in the next several years.

Williams: This is not new, but the increase of elderly people with acetabular fractures. Coming up with an ideal way to fix these injuries that allows elderly patients to get onto their feet and mobile right away is the issue, as well as which of these injuries need to be fixed and at the same time have a hip joint replaced.

There are specialty plates for pretty much any other part of the body, but pelvis has lagged behind. Mainly that’s because the anatomy is so complicated that it’s hard to create a specialty plate as you would in a distal tibia or proximal humerus.

A minimally invasive approach, as far as acute trauma goes, is surgeon-dependent. There’s been a push since the 1980s, and we use it as often as we can to preserve soft tissues around the broken bone and the traumatized area that’s already going to have a hard time healing, but it’s more injury- and surgeon-dependent than it is patient-requested.

BONEZONE: What are some of your most significant challenges in using new trauma/fracture repair devices?

Johnson: We have a bunch of new implants, but the average doctor doesn’t have the time or impetus to go to a course and learn how to use that implant. He sees it, reads the book and then goes in and tries it. There’s always a complication rate that is associated with the implant. It takes a while for that to drop off.

Also, significant challenges for trauma surgeons are the pelvic fracture, the acetabular fracture and the proximal femur. The pelvis is complex – it’s unstable when injured. Repair devices are coming along, but they haven’t changed tremendously for the pelvis. I see a fair number of failed fixations of the pelvis from the minimally invasive technique. If you can show someone a device to take care of a difficult problem, you’ll sell implants all day long.

Vallier: Cost is a big one. New technology tends to be more expensive than whatever it’s supplanting, and it may or may not have supporting research evidence. We’re under pressures from our hospitals to be cost-effective. We want to do the best thing for our patients but we need to find that balance of using new products in a cost-effective way. Many on the market are replaced by something else even before you have time to see whether they would’ve been cost-effective. A lot of old standby things that are less expensive and less flashy may work just as well. I see opportunities for hospital systems and academic institutions to partner more with industry on studies. Rather than just saying, “Oh, they’re selling a product and it’s something new, so we’ll try that,” we have to look at the different stakeholders in the mix and cost pressures. Everybody faces these different challenges and is trying to figure out how to work effectively, yet not shut down new technology. We need to continue to study things to grow the field.

Williams: There was a device on the market for a short while that everybody loved, called the modular blade plate. It was pulled off the market during testing and was not re-released; I’m not aware that any other company has tried to copy it. It combined the fixed angle, bone preserving principle of a traditional 95 degree blade plate with the DCS, which is easier to implant, but removes much more bone. The modular blade plate looked and functioned like a blade plate but the instrumentation was more forgiving, similar to the DCS. If that device were remanufactured, it would be a big winner.

BONEZONE: What should trauma manufacturers know as they prepare to serve your needs?

Johnson: If they don’t interact with an academic organization like the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons, AO North America or the Orthopaedic Trauma Association, they have a responsibility to teach surgeons how to use these implants correctly, not just market it and drop it into the hospital then have the guy struggle with it and just get the payment from the hospital. It’s the manufacturers’ obligation to educate the surgeon on how to use the implant.

Vallier: We have a lot of opportunity to partner together; we want to work with you. We want our patients to get well. We want to have instrumentation that’s easy to use and reusable, so there’s not a lot of waste, so that when we do use your implants, we’re keeping implant costs to a minimum. So we’re trying to maybe not have ten different clavicle plates, but rather one or two.

We’ve been making a big push at the Orthopaedic Trauma Association in trying to work with our industry partners. In some ways, industry is under a lot of scrutiny. In the media, they’re catching a bad rap that the physicians are aligned with them, but we do need to align with them because they need to know what issues we’re facing in order to do an effective job. It’s silly to think that we’re not going to talk or work together, but not to have creepy financial connections too.

We want to create educational and research opportunities to advance the field, but do it in a way that’s transparent and that uses maybe an umbrella organization without a direct connection between a recipient and the donor.

Williams: For the most part, I use standard small fragment and large fragment sets and don’t rely a ton on new techniques and new implants. The market is pretty saturated, and each iteration has subtle improvements.

The newest iteration of specialty plates offers polyaxial locking capabilities and there are a ton available in the 2.7 and 3.5 mm options, but they’re really aren’t a lot of 4.5 options for the proximal tibia.

In the newer generation nails, each iteration makes the locking options at the top and bottom of the nail better so you can increase your indications for nailing. It used to be that nails were only used for shaft fractures, or injuries that weren’t right at the top or right at the bottom of the bone. The newest sets have increased our ability to nail extremely proximal, distal fractures. Only one or two companies come to mind that make a type of nail called a piriformis injury or on-axis femoral nail, with the ability to do reconstruction fixation into the femoral head. Most reconstruction femoral nails are off-axis or trochanteric entry nails. It would be nice if we had a couple more options for piriformis entry (or on-axis) reconstruction nails.